Last September in

Josh Marshall on Google, I wrote:

a quick note to direct you to Josh Marshall's must-read A Serf on Google's Farm. It is a deep dive into the details of the relationship between Talking Points Memo, a fairly successful independent news publisher, and Google. It is essential reading for anyone trying to understand the business of publishing on the Web.

Marshall wasn't happy with TPM's deep relationship with Google. In

Has Web Advertising Jumped The Shark? I

quoted him:

We could see this coming a few years ago. And we made a decisive and longterm push to restructure our business around subscriptions. So I'm confident we will be fine. But journalism is not fine right now. And journalism is only one industry the platform monopolies affect. Monopolies are bad for all the reasons people used to think they were bad. They raise costs. They stifle innovation. They lower wages. And they have perverse political effects too. Huge and entrenched concentrations of wealth create entrenched and dangerous locuses of political power.

Have things changed? Follow me below the fold.

Now in

How Facebook Punked and then Gut Punched the News Biz Marshall is still not happy with Google, although the relationship is one he can live with. But he's really thankful he never had much of a relationship with Facebook:

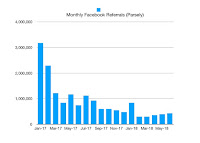

Our total social network traffic is down from the highs of 2016 and early 2017. But not that much. Indeed, if you go back to the Spring of 2015, our total social platform numbers are close to identical to what they were in the Spring of 2018. The difference is that in 2015 Facebook was the biggest source of social referrals and delivered roughly five times as much as the next runner up, Twitter. Today Twitter comes in first and it delivers more than twice as many visits as Facebook.

This drop in traffic is common to all news sites; Marshall was responding to

The Great Facebook Crash by Will Oremus describing the same drop at

Slate. It is the result of

Zuckerberg's attempt to "fix Facebook" with changes that:

will de-prioritize videos, photos, and posts

shared by businesses and media outlets, which Zuckerberg dubbed “public content”, in favor of content produced by a user’s friends and family.

Marshall's strategy is audience- rather than scale-based, in this it is similar to

The Economist's, which has been very successful. The effect of the strategy can be seen in the greater importance of Twitter in TPM's referrals than in the average top site. He contrasts relationships with Facebook and Google:

The first should be obvious: you can’t build businesses around a company as unreliable and poorly run as Facebook. ... There’s no news publisher entitlement to Facebook traffic. And Facebook is a highly unreliable company. We’ve seen this pattern repeat itself a number of times over the course of company’s history: its scale allows it to create whole industries around it depending on its latest plan or product or gambit. But again and again, with little warning it abandons and destroys those businesses. ... But Google operates very, very differently. It has built massive businesses in advertising and other media related fields. It clearly exercises monopolistic power. But its presence, business models and partnerships are much more consistent and

reliable. ... Despite being one of the largest and most profitable companies in the world Facebook still has a lot of the personality of a college student run operation, with short attention spans, erratic course corrections and an almost total indifference to the externalities of its behavior.

Marshall was early in the Web publishing business, starting TPM in 2000. His long experience and willingness to write about it make his observations on the business extremely valuable. Go read his

whole post.

You should also read his post from last April,

Data Lords: The Real Story of Big Data, Facebook and the Future of News:

[The New York Times, the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal] are all in the data collection and sale business. Indeed, TPM is too – not directly at all but because of the ad networks (like Google and others) we have no choice but to work with. ... the issue is one of diversity of revenue streams. Each of those big publications mentioned has at least three big revenue sources ... They have premium advertisers for which the kind of data we’re talking about has limited importance. They

also have subscriptions. The final bucket is made up of advertising that is heavily reliant on data and targeting.

The difference is that Facebook is almost 100% reliant on advertising which is not only reliant on data and targeting but reliant on the most aggressive kinds of data collection, tracking and targeting. That is Facebook’s entire business. Anything that cuts deeply into that model and advantage represents an existential threat.

Marshall's main point is:

Almost every publication participates in the data economy. But the data

economy is almost universally a bad thing for publications, especially

ones that have real audiences.

He explains why this is so in considerable detail, so go read

this post too.

3 comments:

"Facebook isn’t a mind-control ray. It’s a tool for finding people who possess uncommon, hard-to-locate traits, whether that’s “person thinking of buying a new refrigerator,” “person with the same rare disease as you,” or “person who might participate in a genocidal pogrom,” and then pitching them on a nice side-by-side or some tiki torches, while showing them social proof of the desirability of their course of action, in the form of other people (or bots) that are doing the same thing, so they feel like they’re part of a crowd." from Cory Doctorow's Zuck’s Empire of Oily Rags, which is well worth a read.

The collapse in Facebook's stock price, after only 42% y-o-y earnings growth, has inspired Josh Marshall to interesting analysis posts here, here, and here so far. Well worth reading.

Josh Marshall again provides one of the interesting posts sparked by the lawsuit against Facebook for fraudulently inflating the viewership of video on their platform:

"Facebook was dramatically exaggerating how many people watched their videos and how long they watched them. This is not new information. This came out in 2016. At the time my colleagues and I laughed because they called it a “discrepancy”. Calling this a “discrepancy” is a bit of a stretch. In the advertising world, reporting metrics are the currency, almost literally. If you’re a lawyer and double bill your hours for years, that’s not a discrepancy. It’s fraud, certainly if you’re doing it intentionally. The key was that Facebook was so big that they had largely gotten away with generating their own metrics. They didn’t have to submit their numbers to any kind of third-party verification. What this lawsuit now alleges is that Facebook knew for roughly a year that their numbers were wrong before they told anyone."

Post a Comment