|

| Source |

about the reaction to the 1998 murder of gay University of Wyoming student Matthew Shepard in Laramie, Wyoming. The murder was denounced as a hate crime and brought attention to the lack of hate crime laws in various states, including Wyoming.The new play, Here There Are Blueberries, is on tour after a 2022 premiere at the La Jolla Playhouse and a 2024 run at the New York Theatre Workshop. Vinson Cunningham reviewed the New York production in The Chilling Truth Pictured in “Here There Are Blueberries”:

An example of verbatim theatre, the play draws on hundreds of interviews conducted by the theatre company with inhabitants of the town, company members' own journal entries, and published news reports.

There’s something awful about a lost picture. Maybe it’s because of a disparity between your original hope and the result: you made the photograph because you intended to keep it, and now that intention—artistic, memorial, historical—is fugitive, on the run toward ends other than your own. The picture, gone forever, possibly revived by strange eyes, will never again mean quite what you thought it would.The play dramatizes the process archivists at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum went through to investigate an album of photographs taken at Auschwitz. Photographs from Auschwitz are extremely rare because the Nazis didn't want evidence of what happened there to survive.

Below the fold I discuss the play and some of the thoughts it provoked that are relevant to digital preservation.

|

| Source |

Developing one of these plays is a painstaking process, The actors conduct extended interviews with the people they will represent, and the playwrights select and organize quotes from the interviews. And, in the case of London Road, set them to music.

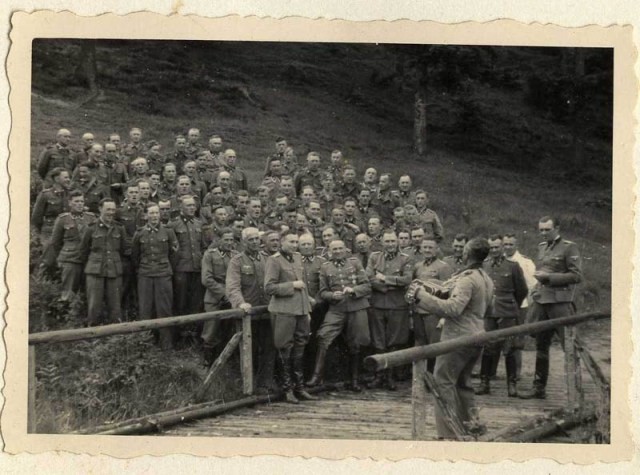

In this case most of the participants were archivists at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum who, in 2006, received an offer to donate an album of photographs from Auschwitz. Initially skeptical, archivist Rebecca Erbelding rapidly established that the more than 100 images in the album documented the life of Karl-Friedrich Höcker during the period from May to December 1944 when he served as the adjutant to Richard Baer, the last commandant of Auschwitz. Thus the album became known as the Höcker Album.

|

| Source |

in the company of young women—stenographers and typists, trained at the SS school in Obernai, who were known generally as SS Helferinnen, the German word for (female) "helpers".

|

| Richard Baer, Josef Mengele, & Rudolf Höss |

The survival of the album is remarkable. A US Army counter-intelligence officer was assigned to Frankfurt in the aftermath of the war. His story is that, unable to find a official billet, he occupied an abandoned apartment in whose trash he found the album. It wasn't until 2006, six decades later, that he offered it to the US Holocaust Memorial Museum.

|

| Source |

Between 15 May and 9 July 1944, over 434,000 Jews were deported on 147 trains, most of them to Auschwitz, where about 80 percent were gassed on arrival.Despite the celebration, the operation was less than completely successful. Before it was stopped by Miklós Horthy, the Regent of Hungary, it had only succeeded in transporting about 434,000 of Hungary's about 825,000 Jews, and killing about 350,000 of them.

| Source |

document the disembarkation of the Jewish prisoners from the train boxcars, followed by the selection process, performed by doctors of the SS and wardens of the camp, which separated those who were considered fit for work from those who were to be sent to the gas chambers. The photographers followed groups of those selected for work, and those selected for death, to a birch grove just outside the crematoria, where they were made to wait before being killed.The Auschwitz Album's survival is equally remarkable:

The original owner of that album, Lili Jacob (later Zelmanovic Meier), was deported with her family to Auschwitz in late May 1944 from Bilke (today: Bil'ki, Ukraine), a small town near Berehovo in Transcarpathian Rus which was then part of Hungary. They arrived on May 26, 1944, the same day that professional SS photographers photographed the arrival of the train and the selection process. Richard Baer and Karl Höcker arrived at Auschwitz mere days before the arrival of this transport. After surviving Auschwitz, forced labor in Morchenstern, a Gross-Rosen subcamp, and transfer to Dora-Mittelbau where she was liberated, Lili Jacob discovered an album containing these photographs in a drawer of a bedside table in an abandoned SS barracks while she was recovering from typhus.Because it was taken the day Jacob arrived, she:

first found a photograph of her rabbi but then also discovered a photo of herself, many of her neighbors, and relatives, including a famous shot of her two younger brothers Yisrael and Zelig Jacob.She took the album with her as she immigrated to the United States. In 1983 she donated it to Yad Vashem, after which it was published.

|

| Höcker & Helferinnen |

Höcker served 18 months in a British POW camp before resuming his pre-war life as a bank cashier. In 1963 he was tried in Frankfurt and sentenced to 7 years:

Höcker denied having participated in the selection of victims at Birkenau or having ever personally executed a prisoner. He further denied any knowledge of the fate of the approximately 400,000 Hungarian Jews who were murdered at Auschwitz during his term of service at the camp. Höcker was shown to have knowledge of the genocidal activities at the camp, but could not be proved to have played a direct part in them. In post-war trials, Höcker denied his involvement in the selection process. While accounts from survivors and other SS officers all but placed him there, prosecutors could locate no conclusive evidence to prove the claim.In 1989 he was tried again and sentenced to 4 years:

On 3 May 1989 a district court in the German city of Bielefeld sentenced Höcker to four years imprisonment for his involvement in gassing murders of prisoners, primarily Polish Jews, in the Majdanek concentration camp in Poland. Camp records showed that between May 1943 and May 1944 Höcker had acquired at least 3,610 kilograms of Zyklon B poisonous gas for use in Majdanek from the Hamburg firm of Tesch & Stabenow.Obviously, many of the thoughts provoked by the play are relevant to current events, about how one would have behaved and how bureaucrats can compartmentalize their lives so as to claim ignorance of the activities they administer, as Höcker did in his first trial:

I only learned about the events in Birkenau…in the course of time I was there… and I had nothing to do with that. I had no ability to influence these events in any way…neither did I want them, nor carry them out. I didn’t hurt anybody… and neither did anyone die at Auschwitz because of me.The other set of thoughts are relevant to digital preservation. Obviously, the negatives of the photographs in the two albums did not survive. Individual prints from the negatives did not survive. The images survive because in both cases a set of prints was selected and bound into an album, which protected them. Once the albums had been discovered, their survival for many decades was well within the capabilities of the officer and the survivor. "Benign neglect" was all that was needed. A few of the prints suffered visible water damage, but this didn't impair their value as historical documents.

Compared to WW2, many more images and videos documenting the events currently under way in Ukraine, Gaza, Myanmar, Syria, and many other places are being captured. But they are captured in digital form, and this makes their survival over enough decades to be used in war crimes trials and as the basis for histories unlikely. They may be collected into "albums" on physical media or in cloud services, but neither provides the protection of a physical album. The survival for many decades of such digital albums is well beyond the capabilities of those who took, or who found them. This fact should allow the perpetrators of today's atrocities to sleep much easier at night.

Before they were delivered to preservation experts the survivor and the officer had custody of their albums for four and six decades respectively. Four decades is way longer than the expected service life of any digital medium in common use; images and video on physical media require the custodian proactively to migrate them to new media at intervals. "Benign neglect" does not pay the rent for cloud storage, and trusting to the whims of the free cloud storage services is likely to be neglect but hardly benign.

To improve the chances of current-day albums analogous to the Auschwitz Album and the Höcker Album we need a consumer-grade long-lived storage medium that is cheap enough for everyday use. Alas, for the reasons I set out in Archival Storage, we are extremely unlikely to get it.

No comments:

Post a Comment